ʻO EQUATIONAL SENTENCES

Learning The ʻO Equational Sentence Structure - Pepeke ʻAike ʻO

This is one of the most fundamental sentence structures in the Hawaiian language. The Hawaiian grammatical term for this structure is "Pepeke ʻAike ʻO. It is used to say that something is something else. It' not that something just has a particular characteristic and is in the category of some quality; that's what the He Class Inclusional Sentence (Pepeke ʻAike He) does.

There are two phrases that follow the ʻO in the structure and the interpretation (and translation) is that "A is B"

Form And Usage Of The ʻO Equational Sentence

When expressing that one thing is another thing, the form of the sentence is:

ʻO + Thing A + Thing B

Note that since Thing A and Thing B are "equal" to each other, the order in which they're stated doesn't change the underlying meaning of the sentence. You may choose to "front" one, or the other, of the two things for emphasis. Equational examples include:

- ʻO Iokpea kaʻu inoa - Iokepa is my name

- ʻO wai kou inoa? - What is your name?

- ʻO ka iʻa kaʻu mea ʻai punahele - Fish is my favorite food

- ʻO ka lā nani loa keia lā - It is the most beautiful day today

- ʻO keia lā ka lā nani - Today is the most beautiful day

- ʻO Sally ke kumu - Sally is the teacher ("Sally" doesn't need a separate ʻo name/subject announcer in this order)

- ʻO ke kumu ʻo Sally - The teacher is Sally (Notice the name/subject announcer ʻo in front of Sally in this order)

- ʻO keia ka ʻaina ʻono nui - This is the best meal

- ʻO kēlā wahine ka wahine ʻakamai loa - That woman is the smartest woman

- ʻO kaʻu hoa loa kaʻu ʻīlio - My best friend is my dog

Notice in the examples above that the ʻO Equational structure implies "the" and not "a". In other words, "Sally is the teacher"; not simply "a teacher", one of many teachers, but "the teacher" (perhaps

the teacher of this class. True, she is

a teacher but here we're calling out the fact that, in this case, she is

the teacher.)

Using Mea In The ʻO Equational Sentence

The word "mea" means "thing", "object", "person", and is a general placeholder for, essentially, anything. It's often used in the ʻO Equational sentence to establish a lead-in to an explanation. Mea may have a modifying relative clause associated with it. Consider these examples:

- ʻO Sally ka mea me ka lole ʻahinahina - Sally is the one with the gray dress

- ʻO Kāwika ka mea ma ka ʻaoʻao hema - Kāwika is the one on the left side

Ka Mea With A Relative Clause

You can add a relative clause to describe an action associated with "ka mea" as in these examples:

- ʻO Kamil ka mea e paʻa nei i ka puke - Kamil is the one (now) holding the book

- ʻO ka mea me ka lauoho ʻulaʻula o Kalua i ʻike ai i ʻo Jeff - The one with the red hair that Kalua saw is Jeff

- ʻO Sally ka mea aʻo aku ma ke kula - Sally is the one who teaches at the school

- ʻO kēlā mau pōpoki nā mea ana i hānai ai ma ka paka i ka pō aku nei - Those are the cats that were the ones she fed in the park last night

Negative ʻO Equational Sentences

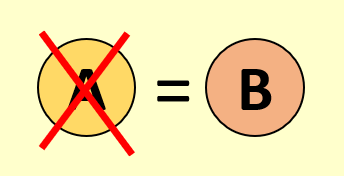

A negative ʻO Equational sentence simply states that something is NOT something else. The only consideration is as to what is being negated, Thing A or Thing B. The thing that is negated is preceded by ʻAʻole and it moves to the front. That leaves the ʻO and the thing that's not negated in the back.

Thing A IS Thing B --> NOT Thing A IS Thing B or, perhaps, NOT Thing B IS Thing A

When thinking about what is being negated (and, hence, what moves to the front, preceded by ʻAʻole), think about the concept underlying the statement youʻre making. Here are some examples, along with a context to consider:

You're looking at a cat and you tell your friend:

ʻO kēlā ka pōpoki - That is a cat

You're looking at a dog and you tell your friend:

ʻAʻole ka pōpoki ʻo kēlā - Not a cat is that (That is not a cat). You're emphasizing the type of animal, it's not a cat.

Your friend is trying to pick a cat out of of a group of dogs. They point to one of the animals. You say:

ʻAʻole kēla ʻo ka pōpoki - Not that is a cat (That is not a cat). You're emphasizing the fact that "that", the thing you're friend is pointing to, is not a cat.

Notice that in each negative example above, the ʻo was present in the middle of the sentence. The negated thing "moved up front", preceded by ʻaʻole. Here's another set of examples:

As you pass by a house, a large dog and a small dog run out to the fence and begin barking. Your friend asks, "Those people have a big guard dog!". You know that the big dog actually belongs to the neighbor and you say:

ʻAʻole kā lākou ʻīlio ke kiaʻi - The guard is not their dog

Your friend wonders whether or not the little dog could, possibly, be a guard dog. You respond:

ʻAʻole kiaʻi kā lākou ʻīlio - Their dog is not a guard